ICBC Adjusters Don't Speak Your Language: How to Translate Medical Terms Into Approvals

You spent years learning sophisticated medical terminology. You can describe precisely what's happening in your patient's body using technical language that impresses colleagues and demonstrates your expertise.

But here's the brutal truth: That same medical language is killing your ICBC approval rates.

ICBC adjusters don't speak your language. They don't understand your special tests, range of motion measurements, or neurological assessments. When you write detailed clinical findings, they see extensive medical jargon that doesn't justify continued treatment.

It's time to learn the language ICBC actually understands: functional limitations.

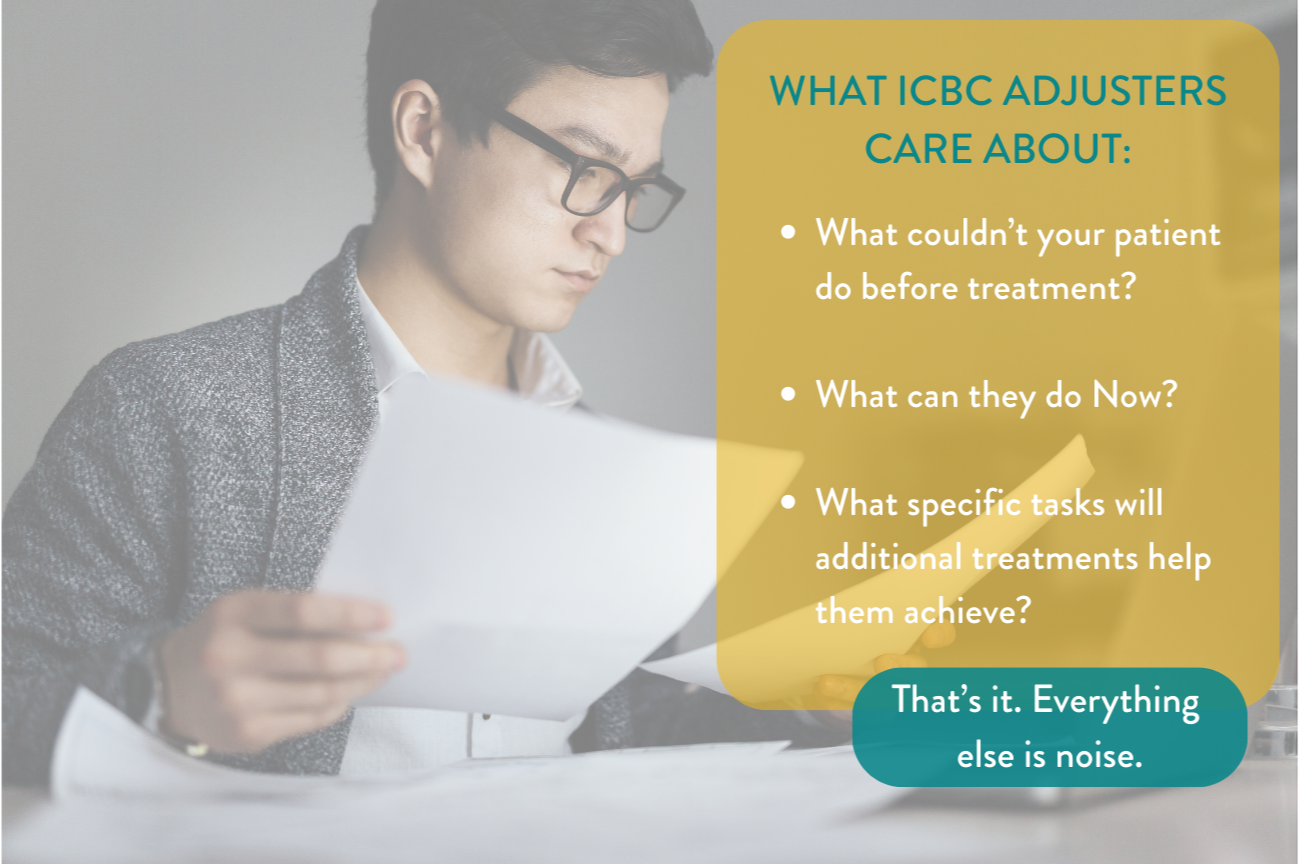

What ICBC Adjusters Actually Care About

Forget everything you know about the medical documentation you learned in school. ICBC adjusters care about exactly three things:

What couldn't your patient do before treatment?

What can they do now?

What specific tasks will additional treatments help them achieve?

That's it. Everything else is noise.

The Translation Problem

Let's look at how medical language translates (or doesn't translate) to ICBC approvals:

What You Write: "Patient demonstrates positive Spurling's test with decreased cervical rotation of 15 degrees and grade 3/5 muscle weakness in C6 distribution."

What ICBC Hears: "Extensive medical testing that doesn't explain why the patient needs more treatment."

What You Should Write: "Patient cannot check blind spots while driving due to neck stiffness and cannot lift grocery bags from car to counter due to arm weakness."

See the difference? One focuses on clinical findings. The other focuses on real-world impact.

Real-World Translation Examples

Example 1: Lower Back Pain

Medical Language: "Patient presents with lumbar facet joint dysfunction, positive prone instability test, and decreased lumbar flexion of 20 degrees."

ICBC Translation: "Patient cannot sit at work computer for more than 15 minutes without standing, cannot lift laundry basket, and requires assistance getting out of low chairs."

Example 2: Shoulder Injury

Medical Language: "Positive empty can test, impingement syndrome with subacromial bursitis, and 30% decrease in shoulder flexion ROM."

ICBC Translation: "Patient cannot reach overhead to retrieve dishes from cupboards, cannot fasten bra behind back, and cannot lift work bags into car trunk."

Example 3: Neck Injury

Medical Language: "Cervical facet joint restriction C4-C6, positive upper limb neurodynamic test, grade 2 joint dysfunction."

ICBC Translation: "Patient cannot turn head to check blind spots while driving, cannot sleep through night due to positioning difficulties, and cannot carry groceries with affected arm."

The Functional Assessment Questions That Matter

Stop asking about pain levels. Start asking about function:

Instead of: "Rate your pain from 1-10" Ask: "What activities have you stopped doing since the accident?"

Instead of: "Does this movement hurt?" Ask: "What tasks at work have become difficult or impossible?"

Instead of: "Where do you feel pain?" Ask: "What do you need help with now that you used to do independently?"

Common Translation Mistakes

Mistake #1: Using Acronyms

Don't Write: "Patient has positive SLR, negative FABER, and restricted PROM" Write: "Patient cannot bend forward to tie shoes, has difficulty getting in/out of car, and cannot reach feet for washing"

Mistake #2: Focusing on Clinical Tests

Don't Write: "Improved joint play C5-C6, negative compression test" Write: "Patient can now turn head to check blind spots and sleep through night without waking from neck stiffness"

Mistake #3: Percentage Improvements

Don't Write: "30% improvement in cervical rotation" Write: "Patient can now look over shoulder to parallel park, previously impossible”

Breaking Goals Into Achievable Chunks

ICBC wants to see progress in small, measurable steps. Don't set massive goals like "return to full work duties." Break it down:

Poor Goal: "Improve neck mobility" Better Goal: "Patient will be able to check blind spots while driving safely within 4 treatments"

Poor Goal: "Reduce back pain" Better Goal: "Patient will sit at work desk for 1-hour periods without breaks within 6 treatments"

Poor Goal: "Increase shoulder strength" Better Goal: "Patient will lift and carry 10-pound grocery bags from car to kitchen counter within 3 treatments"

The Before and After Strategy

Your most powerful documentation tool is the before/after comparison. ICBC needs to see clear functional progress:

Before Treatment: "Patient required assistance getting dressed, couldn't drive to work, and needed help carrying groceries."

After 8 Treatments: "Patient now dresses independently, drives to work daily (20-minute commute), and carries groceries but still needs help with overhead reaching."

Goals for Additional Treatment: "Patient will independently retrieve items from overhead kitchen cupboards and return to stocking shelves at work (involves reaching to 6-foot height)."

The Power of Specific Daily Activities

Generic functional goals don't impress ICBC. Specific daily activities do:

Generic: "Improve sitting tolerance" Specific: "Sit through 2-hour work meetings without standing breaks"

Generic: "Increase lifting capacity" Specific: "Load/unload 25-pound boxes from delivery truck at work"

Generic: "Better sleep quality" Specific: "Sleep 6 consecutive hours without waking from positioning discomfort"

Work-Specific Documentation

If your patient works, tie everything back to specific job demands:

Office Worker: Focus on sitting tolerance, computer positioning, reaching for files

Retail Worker: Focus on standing tolerance, lifting boxes, reaching shelves

Tradesperson: Focus on tool use, climbing, carrying materials

Healthcare Worker: Focus on lifting patients, standing shifts, reaching equipment

The Homemaking Connection

Don't ignore homemaking activities - they're legitimate functional goals:

Cooking meals (standing tolerance, reaching, lifting)

Cleaning house (bending, reaching, carrying)

Laundry (lifting, reaching, carrying)

Grocery shopping (walking, lifting, reaching)

Childcare (lifting, bending, carrying)

Self-Care Documentation

Basic self-care activities are powerful documentation tools:

Bathing/showering independently

Dressing without assistance

Personal grooming (hair, makeup)

Getting in/out of bed independently

Walking up/down stairs safely

The Language ICBC Understands

Here are phrases that translate well to ICBC:

"Patient can now..."

"Previously unable to..."

"Will be able to complete..."

"Required assistance with... now independent"

"Cannot perform work duty of..."

"Unable to complete homemaking task of..."

"Needs help with self-care activity of..."

Documentation That Builds Cases

Each treatment note should build on the last, showing progressive functional improvement:

Treatment 4: "Patient can now walk to mailbox (previously required assistance)"

Treatment 6: "Patient can now walk around block once (building on mailbox achievement)"

Treatment 8: "Patient can now complete grocery shopping trips under 1 hour (building on walking tolerance)"

The Bottom Line

ICBC adjusters aren't trying to deny legitimate treatment. They're trying to understand why continued treatment is medically necessary using the only language they know: functional impact.

Your clinical expertise is valuable. Your ability to translate that expertise into functional language determines whether your patients get the treatment they need.

Stop speaking medical. Start speaking functional. Your approval rates will thank you.

Ready to master the language ICBC actually understands? Get our complete "Understanding the ICBC Enhanced Care Model" guide for just $1 and learn the exact functional documentation strategies that get approved every time.

[Get Your $1 ICBC Enhanced Care Guide Now →]